Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

Gender-based violence continues to be a major human rights issue around the world. No country — even those that boast the highest levels of gender equality — has fully eradicated GBV. Regardless of class, ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, disability status, or culture, it affects one out of every three women and girls.

It doesn’t have to. Every day, millions of people, groups, and organisations work to bring change at the family, community and national levels. Here are 16 solutions to gender-based violence (GBV) that we’ve come across in our own work to end violence against women and girls.

1. Educate, educate, educate

Education at every level is one of the key solutions to gender-based violence. GBV is a learned behaviour. That means it can be unlearned. Every other item on this list is, in essence, a form of education. Women need to know their rights, how to report violence, and how to reject harmful gender norms. Men need to know how patriarchal structures create these harmful gender norms, and how their behaviour may be contributing to an unhealthy dynamic. Communities need to know what GBV looks like and how to react when they see it. Facilitators need to know the root causes of gendered violence at a national, regional and community level.

2. Understand the specific root causes of GBV in each country and community

While there are some consistent elements of gendered violence from one context to the next, we need to examine the particulars of a given situation in order to shift behaviours and attitudes. The more specifically we can understand the systems of marginalisation and patriarchal structures in place in a given community (especially in some of the countries with the worst track records for women’s rights), the better we can find ways of addressing those systems and finding sustainable ways for people of all genders and generations to break harmful habits.

3. Believe and support survivors

One of the biggest barriers to ending GBV today is that survivors are often not believed when they speak up. This can create additional stress and abuse for those who take that incredibly brave step — the first step needed to break the cycle of GBV — and also discourage other people suffering gendered violence from speaking out. This not only harms those experiencing violence, but also entire communities. Gender-based violence thrives in silence, and one of the biggest things we need to do to end GBV is to first understand how widespread the problem is.

Beyond believing survivors, we also need to ensure that they have the support they need after reporting their abuse. Even if a woman is believed, she can also be stigmatised for being attacked. No one who suffers from GBV should suffer further through societal exclusion. This is especially true for survivors of rape and sexual assault. At minimum, survivors of abuse should have access to quality healthcare (including psychosocial support), legal services, economic assistance, and shelters or safe spaces for themselves and their children.

4. Pay special attention to high-risk groups

We know that GBV can happen to anyone, although women are more likely to be targeted than men. Within that, however, are a number of different identities that can make certain women even more vulnerable to violence. A 2018 study from UNFPA reveals that girls and young women with disabilities face up to 10 times more gender-based violence than those without disabilities. Those with intellectual disabilities are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence. What’s more, Indigenous women, LGBTQIA+ women, or women who are not of an area’s predominant race, class, or ethnicity, are all at higher risk for attack.

5. Find non-harmful alternatives to harmful traditions

Some of the most common types of GBV are not even seen as such. For instance, female genital mutilation (FGM) has been regarded as a traditional rite of passage for young women in areas such as Marsabit in northern Kenya. Despite the country outlawing FGM in 2011, Concern Kenya’s Education Manager Agnes Angolo explains it still happens “to nearly 100% of the girls here.” Often these girls are as young as nine or 10 years. Those who don’t undergo the process can become outcasts.

A number of approaches are necessary to fight a harmful tradition like FGM, including engaging men as allies and strengthening community accountability (more on both below). However, a study in the journal Reproductive Health notes that one of the key solutions to replacing these traditions is to find alternative ritualistic programmes (ARPs). There are other ways of symbolising a girl’s transition into womanhood, and finding a healthy and safe way of doing so will keep the spirit of the tradition alive while adapting it for what we know now to be a risky practice.

6. Challenge other gender norms

There are other gender norms that aren’t as violent or harmful, but still contribute to GBV. Many of these seem inoffensive at face value, such as the stereotype that women tend to the home while men go to work; or the notion that certain activities are “for boys” or “for girls.” However, all of these norms and stereotypes support a larger system of inequality between the genders that, at its worst, can turn violent. Much like a pandemic, we have to bring all cases — severe and mild — under control in order to halt the spread.

7. Engage men as allies and partners

Women need to be supported and empowered, however any solution to GBV that doesn’t engage men and boys is only going to work so well before it is undermined. Through Concern’s partnership with Sonke Gender Justice, we are implementing approaches to prevent GBV through Engaging Men on Gender Equality in ten countries. The approach supports both men and women in transforming their attitudes and behaviours by questioning what it means to be a man or a woman, understanding how traditional beliefs may not work practically in contemporary society, and ultimately moving couples towards more positive and equal relationships.

8. Focus on community change

Gender-based violence may seem at times like an intimate issue, one that happens behind closed doors and out of the public eye. However, it’s a community’s responsibility to band together in order to end violence — especially against women and girls. This is why Concern works with groups of men and women to foster conversations and workshops around gender equality, with each cohort serving as a mutual support system for one another. We also help launch self-help groups for both men and women, who learn and grow at the same time and are able to be a support system for one another long after they complete a Concern programme. Community accountability, such as father’s groups ensuring that girls (and boys) stay in school, is one of the keys to keeping GBV cases at zero.

9. Keep girls in school

Speaking of keeping girls in school… Child marriage and related forms of gendered violence may prevent girls from finishing their education. We know from data that girls who are missing out on an education are more susceptible to violence, especially at home. A girls’ education should include topics like gender equality, consent, sexual reproductive health, and the notion that her potential in life is equal to that of a man’s. By understanding these concepts and developing practical and intellectual skills alongside them — all facilitated through a safe learning environment — younger generations of girls and women will be more capable of fighting back against GBV.

10. Empower women economically and financially

Many women lack the same financial and economic rights as men, including land ownership and the ability to set up a bank account. Leaving women dependent upon men for basics like their income and livelihoods means that we’re also furthering the idea that women are “less than” their male counterparts. Establishing economic parity between the sexes through initiatives like Village Savings and Loans Associations helps to reduce dependencies, break stereotypes, and build a foundation for widespread gender equality.

11. Give women a seat at the table

One of the biggest factors perpetuating GBV is that many women are excluded at the social and political levels, especially when it comes to designing laws and decisions that impact community life. This means that many new laws and norms continue to exclude women, leaving them vulnerable to the compound interest of ongoing gender disparities. This is true at any level, from a community council’s disaster-preparedness plan to national parliament.

12. Treat GBV as a public health issue

Gender-based violence can affect survivors’ physical and mental health long after the attack itself. Many forms of GBV specifically affect the health of the targets of such violence, including FGM and sexual assault. Survivors need to have access to the resources they need in the wake of these events, such as emergency contraceptives and STD screenings.

For women especially, they should feel safe confiding in a healthcare professional if they are experiencing violence at the hands of a family member or intimate partner. This can be a question initiated by their provider during a checkup, with follow-ups in place if the patient indicates they are at risk. Bringing in the healthcare system of any area (at the local and/or national level) makes GBV not simply a matter of laws and justice, but about the well-being and dignity of all community members.

13. Normalise mental health and psychosocial support systems

This is important for both survivors and perpetrators of GBV. Survivors deserve comprehensive psychosocial support to recover from an act of GBV, whether one-time or protracted. However, perpetrators of GBV also need and deserve resources to build and maintain their own mental wellness. Many perpetrators of GBV are not inherently “bad” or malicious. But, during a crisis — such as a conflict that leads to displacement or a pandemic that leads to lockdowns and job losses — many lack the emotional resilience to navigate the stresses of an uncertain situation. This is especially true for men growing up in cultures where their sense of manhood is questioned if they can no longer provide for their families. We saw this happen a lot among Syrian refugees; mental health programmes and support groups were key to breaking the cycle.

14. Commit to additional safeguards against GBV during crisis and conflict

As we mention above, crises can lead to an influx of GBV. This may be due to men struggling to cope with the undue stress of displacement, war, or a natural disaster. However, there are many other ways that GBV persists during crises. Women are especially vulnerable following an emergency evacuation. Girls may be separated from their families and vulnerable to sexual assault or trafficking. Women may need to flee without their husbands or fathers and serve as the head of family, which leaves them open to both discrimination and abuse. Any emergency response to a humanitarian situation must include elements of safeguarding women and children.

15. Address other intersectional issues including climate change, hunger, and poverty

GBV rarely happens in a vacuum. Many factors at play in a community may increase stress and vulnerability, such as climate change — the effects of which often cause displacement and place stress on available resources. The UN notes that girls living in poverty are 2.5 times more likely to be forced into an early marriage (another form of GBV) in order to reduce the financial burden of their families. The Irish Joint Consortium on Gender Based Violence also links hunger and land access to GBV. There’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg scenario to these factors, however one thing is clear: Addressing GBV in tandem with any of the issues it’s demonstrably linked to will help solve both issues at once.

16. Legislate, legislate, legislate

Many of the advances towards ending GBV are only so effective. Women must be afforded the same legal protections as men in a society, with constitutional amendments to back these rights up for both current generations and those to come. This includes everything from outlawing honour killings and child marriage to guaranteeing land rights and equal pay for equal work, to even bolder moves, such as requiring a country’s governing body to have gender parity. As we’ve seen from examples like the banning of FGM in Kenya, many citizens will ignore these laws, but having them in place means that communities can take on a greater role of accountability, knowing that the law is on their side.

Ending gender-based violence: Concern’s approach

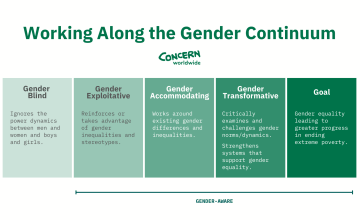

Gender Transformative

Gender equality is one of the most important steps to ending extreme poverty. All of Concern’s programming, from health and nutrition to emergency response, happens through a gender transformative lens. That means we don’t simply work around existing gender inequalities or differences. Instead, we critically examine and challenge gender norms and dynamics in order to build equity and make greater, more sustainable progress towards ending extreme poverty. Where it makes sense, we also build and strengthen systems to support that level of equality.

Malawi: Umodzi

Harmful gender stereotypes and norms are learned behaviours that, with the right approach, can be unlearned. When we brought the Graduation programme to Malawi in 2017, we focused on working with women as the main program participants, but also designed a 12-month curriculum of monthly sessions for women and their husbands or partners called Umodzi (which means “united” in Chichewa). The sessions focused on getting couples to discuss topics such as gender norms, power, decision-making, budgeting, violence, positive parenting, and healthy relationships. By the end of Year 1, couples participating in Umodzi saw an average 10% increase in women participating in major decision-making.

Kenya, Liberia, and Somalia: VSLAs and Women’s Self-Help Groups

We support female-lead VSLAs and Women’s Self-Help Groups in many of the countries where we work, including Somalia, Kenya, and Liberia. Like Graduation, these initiatives are designed to give women greater status and negotiating power at home and within their communities through financial education and empowerment. As the IJC on GBV notes, microfinance and leadership training on their own won't solve GBV. The group aspect of these initiatives leads to greater confidence and empowerment, and also normalises a system of support and culture of transparency around the issues women face in any given community. There is both safety and power in numbers.

Lebanon: Men’s Protection Groups

We also engage men as allies and partners in gender equality. In Lebanon, our Men’s Protection Groups have helped displaced Syrians confront feelings of powerlessness and helplessness — feelings rooted in gender roles and norms that traditionally paint men as strong and emotionless. Over the course of three months, these community-developed committees meet to discuss their own experiences, feelings of helplessness and powerlessness, and methods of what Marshall Rosenberg coined nonviolent conflict resolution. These methods introduce concepts that are new to many Syrian men: self-empathy, empathy for others, and honest self-expression.

Bangladesh: Engaging Men and Boys

Likewise, we’re fighting gender inequality in Bangladesh through Engaging Men and Boys, a programme that trains Change Makers on internalising the root causes and effects of gender inequality (including GBV). Our Change Makers then become advocates for gender equality within their communities, and work with other groups to affect change from within. Change Makers also advocate with local-level community leaders, ward health and development committees, religious leaders, teachers, and government institutions, helping to build the accountability and enforcement needed for Bangladesh’s gender equality laws to hold up and serve the people they’re designed to protect.