Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

How #tradwife myths impact the most vulnerable women around the world.

You’ve likely come across the term on the internet on and off over the last seven years. The phrase “tradwife” is a bit self-explanatory: a combination of the words “traditional” and “wife.” While there are several ways that women have taken on this term since it first became popularised on social media and blogs circa 2016, the general gist is the same throughout: A tradwife is a woman who trades feminism and gender equality for a more “traditional” gendered role: staying home, keeping house, having children, and being generally subservient to her husband.

On TikTok, videos with the hashtag #tradwife have been viewed over 251 million times. Similar videos tagged #trad have been viewed nearly half a billion times. On Instagram, there are nearly 58,000 posts tagged #tradwife, and 1 million posts tagged #trad. The trend is especially popular in the United States (where it also has links to far-right politics and, in some cases, the white supremacy movement). But in recent years, it’s also gained traction in Ireland and the United Kingdom — especially among young women who feel stressed and burned out by the dual mandate of having a career and a family.

Despite the sense of regression with the movement, many women who post as #tradwives on social media argue that their lifestyle is a feminist one. They are, after all, making the choice not to work.

But is it really that simple? Or are many hashtag-tradwives overlooking some significant myths that contribute to a larger, global, issue of gender inequality? And is it possible that this trend is having an impact on the world’s most vulnerable women? Read on for more.

Despite what they think, many tradwives are actually working

And not just through unpaid domestic labour. The most popular tradwives—some of whom also go by the title of “momfluencer”— not only document their daily cooking, cleaning, and caring routines on social media; they monetise them. Before there were momfluencers, there were mommy bloggers who turned their blogs into cottage industries through selling banner ads, sponsored content, and, occasionally, book deals. Today, those income-generating avenues have grown with partnerships that lead to posts on Instagram and TikTok. Some of the most successful creators are even represented by managers who help to broker these deals, which can net the most successful influencers anywhere between $10,000 and $100,000 USD per year.

This is — you guessed it — a job. While tradwife influencers may not go into an office, they are still earning an income (in some cases an incredibly high one) in exchange for their creative output. “Social media influencing is a career trajectory,” Whitman College sociologist Michelle Janning told Insider last year. “It could be that they're not selling a product but selling a version of themselves, and their husband will be getting the sponsorship. [But] it's a contradiction: Their job is to tell people they don't have a job.”

This is already far more than what millions of women forced into “traditional” roles of wife, mother, and homemaker are allowed in many of the countries where Concern works. Only 23% of Somali women participate in the country’s workforce — a figure that has stayed more or less the same for nearly 35 years. Unlike #tradwives, many of whom have university degrees and a marketable set of skills, only 35% of Somali women ages 20-24 have at least some basic education. This is because of the sexist gender norms that keep Somali women and girls out of the classroom and, by extension, out of work.

The inequalities that fuel poverty also determine who does and doesn’t get paid for her work

It’s not that women shouldn’t be fairly compensated for the work they do at home. The World Economic Forum estimates that men work an average of seven hours a day and are paid for six, while women work an average of seven-and-a-half hours per day but are only paid for three. The difference is often the invisible labour of raising a family and keeping a house. (More on that in our gender pay gap explainer.)

However, many of the inequalities that fuel the cycle of poverty are the same inequalities that determine who should be paid for making dinner or cleaning the kitchen. Tradwife creators and momfluencers are generally white, straight, and conventionally attractive. They also have, independent of their influencer-related work, higher-than-average household incomes and key assets (like a high-quality phone or camera) that enable them to monetise their domestic work. Being a traditional housewife may be something that “any woman” can do, but only a small percentage of women have been able to turn that tradition into a lucrative business.

Many #tradwives might forget the income inequalities that were part of the bygone era they’re trying to recreate. These inequalities are still very much part of the here-and-now in countries like Malawi, where the belief that it’s emasculating for a woman to outearn her husband is still strongly held by both men and women.

A picture isn’t always worth 1,000 words

Many tradwives associate their role with a certain 1950s housewife aesthetic. As one influencer, Estee C. Williams, puts it, she “romanticises” her #tradlife by wearing floral-print house dresses, putting on makeup daily, and fixing her short blonde hair into a Marilyn Monroe bob. However, these images of uncomplicated and perfectly-curated moments of cooking, cleaning, and parenting don’t give us the full story.

When Concern launched the Umodzi programme to build gender equality in Malawi, we found that the same gender norms that many #tradwives espouse have sobering implications for women who have been born into these norms. (Most of these women don’t also have the luxury of dressing up like Grace Kelly to vacuum their bedroom.)

“I was just ‘the Thing,’” one woman told us before she and her husband participated in Umodzi. Nearly half of all women surveyed in the Mangochi and Nsanje Districts said they rarely or never spent even small amounts of money on their own, and nearly two-thirds said they never purchased clothing for themselves (or their children) without the permission of someone else. Even more stark are the links between harmful gender stereotypes and gender-based violence: 32% of women surveyed in Malawi experienced emotional, physical, and/or sexual violence from their partner.

I was just The Thing.

Not all women can opt out of traditional roles and gender stereotypes

In a recent article for ELLE Magazine, Anne Helen Petersen talks about the truth behind #trad posts on social media: “Tradwife behaviours aren’t something you can try out like a new morning routine,” she writes. “They seem to require a wholesale ideological conviction that a woman’s primary role is to be the helpmate of her spouse. They demand a subsumption of personal will, an unquestioning eagerness to bend to a man’s desires—and a belief that those who don’t are sinning against God.”

In this way, too, the #tradwife trend is similar to many of the cultural norms and stereotypes held in communities where Concern works. Beyond the aesthetics and romanticisation of the past, the real link between tradwives and many of the women we work with is the depth at which these harmful gender norms run. However, social media #tradwives have something that the women in these countries generally don’t: the ability to walk away. Many of them have college degrees, or at the very least a solid primary and secondary education behind them. They have marketable skills and established name brands. They live in countries that afford women legal rights and protections, especially when it comes to divorce and domestic violence. It may still be a hard decision, but it’s one that they’re able to make.

Who is really hurt by the #tradwife trend?

Let’s be clear: There’s nothing wrong with wanting to spend more time with your family or less time at work — or even opting out of the latter entirely in order to focus on the former. There’s also a difference between mums who stay at home and work with their partner to find balance and equality within their relationship, and #momfluencers who turn their stay-at-home lifestyle into a small industry.

You can have all of this without having to hold the belief that women are inferior or subservient to men. And this is where the global danger of the #tradwife trend comes in. By popularising this belief — especially as an alternative to the stresses of the modern world for young people who are going through the typical growing pains of starting a career, family, and home — the people who hold to #trad ideals are fueling gender inequalities around the world.

Their videos become talking points and propaganda for pundits and politicians in some of the worst countries for women’s rights. They strengthen pre-existing gender inequalities and can even help foster new imbalances. In romanticising a past they never had, these influencers are helping to deny millions of women and girls the future they deserve.

In romanticising a past they never had, these influencers are helping to deny millions of women and girls the future they deserve.

Gender equality: Concern’s response

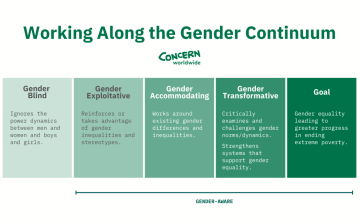

We won’t end poverty until we end gender inequality. At Concern, we see how deep the connections go between gender inequality and issues like poverty, hunger, conflict, and climate change. As such, gender transformation is at the heart of all of our work.

As an international team with programmes in 25 countries, we work with millions of people each year to critically examine and challenge gender dynamics as part of our larger work to end extreme poverty. Building gender equality happens at the community, family, and even individual level: questioning intrinsic gender norms held by both women and men and how equity can coexist with tradition.

Where appropriate, we also build and strengthen local systems to support that level of equality and work with national groups to help those systems transfer to the policy level. All of this together leads to millions of women and girls reached by our work — across a variety of sectors — each year.